This is by no means groundbreaking news, but the fact that this idea is becoming mainstream is encouraging. As climate change becomes a widely accepted fact, we must acknowledge that our weather events are no longer exclusively "acts of God." What's really making wildfires worse is human distortion of natural cycles.

Climate change creates ideal conditions for wildfire through a variety of factors. Drought weakens the trees, and stands that survive are more likely to burn in a fire (as opposed to in the past, when healthy trees withstood smaller, cyclical fires.. Drier air and hotter temperatures strengthen fires' spread. There is more dead vegetation, which is also drier, creating an overabundance of fuel. Water-starved trees cannot fight off bark beetles by producing sap, and fall more quickly to attack. Milder winters no longer kill the beetles in a deep freeze before the next season.

Furthermore, we've disrupted forest ecology through fire suppression. Trees have not only been weakened by drought and infested with beetles, but they've grown much denser than historical norms, allowing beetles to jump easily from tree to tree.

Bark beetles are natural, and their cycle is an important part of forest rejuvenation. But humans have distorted forest ecology to the point that the beetles are no longer in check, and the consequences are evident.

Today we're experiencing the consequences of climate change, beetle kill, and fire suppression all at once - like opening the Pandora's Box of wildfires.

Today we're experiencing the consequences of climate change, beetle kill, and fire suppression all at once - like opening the Pandora's Box of wildfires.

|

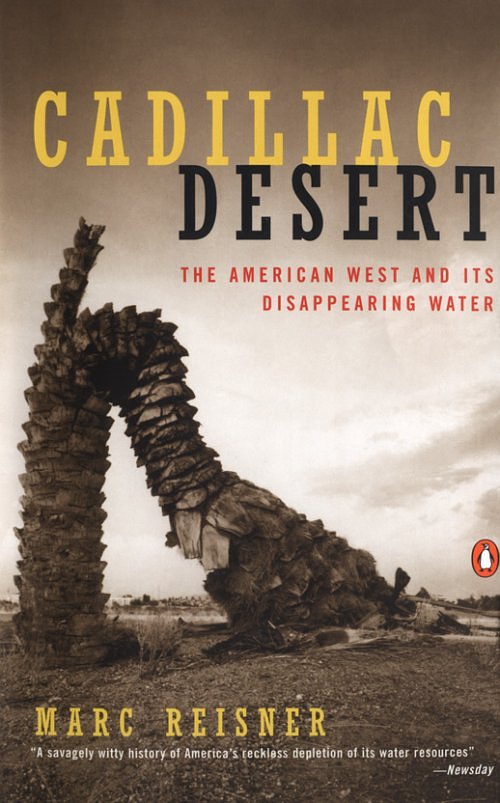

| A forest devastated by beetle kill in Colorado Photo Credit: http://ow.ly/mqqzW |